When we left off last time Ingold and Léschot had created inventions which were changing the Swiss watch industry. Moving the country away from cheap watches, mass produced around the country to quality, in-house mass production.

If you haven’t read the first part of the History of the Swiss Watch Industry, check it out now – I’ll wait!

All caught up, great! Let’s move on.

End of the 19th Century

Despite the number lower quality Swiss watchmakers flooding the market, many Geneva watchmakers still held a good reputation. Unfortunately, with that reputation came a lot of people wanting to make some quick money out of it for themselves.

So, it’s no surprise that counterfeiting took place on a large scale, especially in a country full to the brim with watchmakers. In order to combat the counterfeiting, the Society of Watchmakers pushed the parliament of the Republic and the Canton of Geneva to pass a law setting out the conditions for an authentic Geneva-made watch.

The Geneva Seal was (and still is) used as the seal of authenticity for any Geneva-made watch. Any watch which carries it has had the movement made by a Genevoise craftsman in the Canton of Geneva.

This wasn’t the only anti-counterfeiting measure which was put into place at the end of the 19th Century. The well known seal of quality “Swiss Made” started to appear around 1880 – although it had no legal status at this point.

With new seals of quality in effect, the quality Swiss watchmakers were ready to stand out from the crowd.

The Rise of the Wristwatch

The concept for wristwatches had been around for almost as long as pocket watches, but they were never really taken seriously as a product of their own. In fact, Queen Elizabeth was presented with an “arm watch” from the Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester, in 1571.

Even though a watch worn on the arm appears all the way back in 1571, the Guiness Book of Records credits Patek Philippe with the creation of the first wristwatch – in 1868. This watch was designed for the Countess Koscowicz of Hungary.

The truth is that nobody knows when the first wristwatch was ever created. Chances are, the first one appeared when someone decided to affix a strap to a pocket watch and put it on their arm. It’s also just as likely that the first one ever sold only came about because an aspiring watchmaker saw it and decided to exactly the same thing themselves (as Professor Jaquet and Doctor Chapuis, not-entirely-seriously, suggested in the Technique and History of the Swiss Watch)

But no matter who actually made the first wristwatch, the Swiss helped bring mass appeal to them. In doing so they achieved worldwide recognition, even more so than Swiss watches had ever known before!

Building Wrist Appeal!

There were a few issues to overcome in order to gain mass appeal for wristwatches. Firstly, making them small while keeping them accurate was not easy in the 19th century. And, even if someone managed to make a watch which was small and accurate – people wouldn’t trust it. The general perception of watch buyers was that a watch needed to be a certain size to be accurate.

Secondly, wristwatches are susceptible to hazards that pocket watches aren’t. To simplify it right down – pocket watches are unlikely to get splashed with water or covered in dust when they’re in your pocket, but it is likely when they are on your wrist. If either of those things happened to your watch, it could very easily break the components inside the watch.

Finally, watches were seen as incredibly effeminate, which meant that men were very unlikely to buy them. A quote which sums this up is this one from the the Albuquerque Journal: “The fellow who wears a wrist-watch is frequently suspected of having lace on his lingerie, and of braiding his hair at night.” You wonder what the writer of this piece would have thought of Clint Eastwood and Daniel Craig whenever he saw them sporting a timepiece on their wrist.

Of course, this perception is not really a surprise as most previous wristwatches were made for women at this time. Most of them were called “bracelet watches” and were incredibly beautiful, as well as very feminine.

The only time men would have been noticed wearing wristwatches will have been in the military, because it is much easier to check the time on a watch on your wrist than a watch in your pocket.

So, how could that change? It changed in stages as watchmakers started to make purpose-built wristwatches. A wristwatch design was patented by Dimier Frères & Cie (watches with handles) in 1903. In 1904 Alberto Santos-Dumont, an aviator, asked Louis Cartier to design a watch which would be useful in flights – which unsurprisingly was one which he would wear on his wrist.

One of the biggest changes actually happened in Britain, but via Switzerland. It happened when Hans Wilsdorf moved to London in 1905 and set up a watch business with his brother-in-law, Alfred Davis, called Wilsdorf and Davis. Wilsdorf quickly took an interest in the wristwatch and decided to produce his own line.

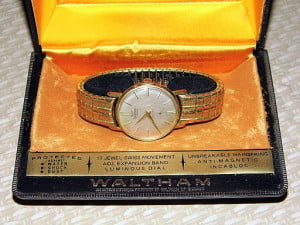

Wilsdorf contacted Swiss company Aegler and placed the largest order ever seen for wristwatches at that time. He sold both men’s and women’s watches with leather straps. Despite the perception of wristwatches as effeminate, these watches found great success. When an expanding bracelet was launched by a popular jewellery firm, he added it to his watches, too… once again with great success.

As he was finding a lot of success with wristwatches in Britain, Wilsdorf wanted to create his own watch brand. He opened an office in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland in 1907 and originally decided to register the name Lusitania – after the most luxurious liner in the world.

This name didn’t last long and in 1908 he registered the name Rolex – mainly because it was “a word easy to memorise.” Wilsdorf wanted to create a brand which would set his watches apart from all others, even though other watches would have very likely included the same parts produced by Aegler.

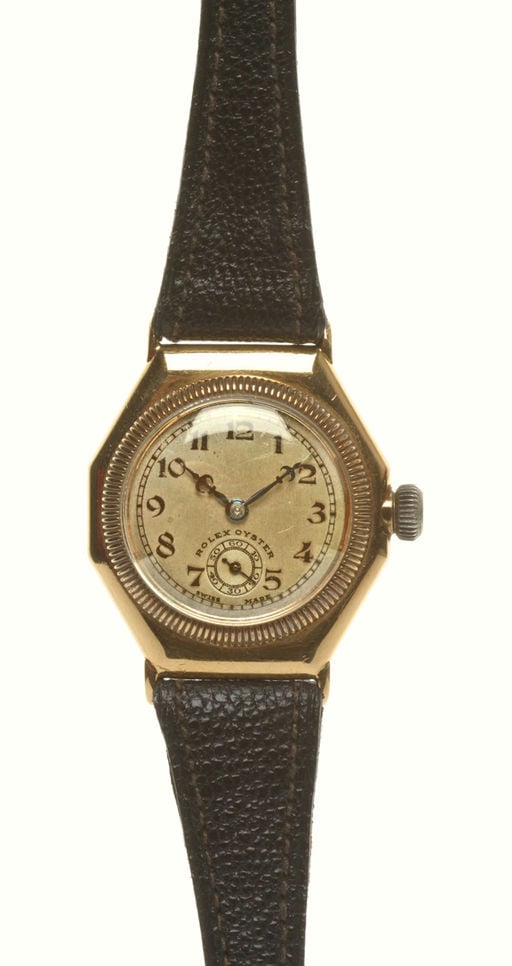

Watches created for Wilsdorf after this point included the trademark “Rolex” – which quickly became a well respected watch brand. They broke new ground, too, with the Rolex of 1910 being the first to receive certification as a chronometer in Switzerland.

The War Changes Everything

During the First World War it soon became apparent that military personnel needed to have a watch on their wrist. The need for precise synchronisation meant that everyone on the ground needed a wristwatch. With many battles taking to the air, military pilots found, just as Alberto Santos-Dumont did, that a watch on your wrist is much more convenient than one in your pocket!

You can read more about the impact of watches during the war in “Watches Which Helped Win Wars”. But one thing which is very interesting is the impact on the perception of wristwatches when the war ended, as conscription meant that practically every working age man in Britain was in the military at some point. This meant that all men returning from the war returned with a wristwatch – and many continued to wear them.

Suddenly wristwatches were no longer seen as flimsy or effeminate and were more likely to be worn by former military personnel than anyone else. The ratio of wristwatches to pocketwatches had almost reversed by 1930 – standing at 50 to 1. With most of these watches produced by Swiss companies, usually Rolex or Omega.

In the Second World War wristwatches were already expected for any members of the military. Rotary, who were founded in Switzerland, produced watches for the British Army during the Second World War, putting one in almost every household in the UK.

Swiss manufacturers were quick to take advantage of the gap in the American market. With all American manufacturers being used for the war effort, Swiss manufacturers were able to pick up customers that the American manufacturers weren’t catering for.

And this time, unlike the previous attempt to flood the market with Swiss watches, the quality of the products was incredibly high.

Swiss Innovations Between The Wars

One reason why Switzerland were so prepared to take over the American watch market is that they weren’t just producing quality watches, they were on the cutting edge of watch technology.

In 1926 Rolex produced their first waterproof wristwatch – the Rolex Oyster. Waterproof pocket watches had been produced previously, but they had not been implemented into wristwatches yet. Wilsdorf brought the rights to a patent for a “screw down crown” to make a waterproof watch, but it wasn’t suitable for a wristwatch to be sold to the public. Thankfully his technicians at Aegler managed too adjust the design and produce a top quality watch.

John Harwood, a watch repairer from Bolton, claimed the patent in England and Switzerland for the first automatic watch. Production started on them in his Swiss factory in 1928 and they worked perfectly, working for 12 hours when fully charged. This heralded a breakthrough in watchmaking, as people had attempted to produce automatic watches since 1770. Including Breguet, who managed to release automatic pocket watches – but had to stop selling them when the public found them unreliable.

Rolex improved upon and incorporated the automatic technology in their watches. By incorporating it in Rolex Oyster they managed to resolve the issue of wear and tear when unscrewing the watch to wind it.

Conclusion

By the end of the 2nd World War, the Swiss Watch industry was in he perfect position. Controlling practically the entire world watch market – in almost every home in the United Kingdom and taking over the American market. This set the Swiss up to be the leaders for the next two decades, almost untouched by anyone else.

Although, something else was going on, too. Swiss watchmakers had opened up the market in Japan and the shared knowledge was the backbone of a burgeoning competitor. The background to this can be read in our blog post on the Swiss Foundations of the Japanese Watch Industry.

In the next part of the History of the Swiss Watch Industry we’ll see how this colleague come competitor almost destroyed the Swiss watch industry and how the industry recovered.

Images: Fourdee, Museumsfoto – Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Joe Haupt, Isabelle Grosjean ZA, Museumsfoto (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum)