One thing everyone in the world knows about watches is that buying a Swiss watch is the nearest to a guarantee of excellence you can get in today’s world. As an advertisement for Zurich Airlines says “Like shopping for a Swiss watch. Hard to make a mistake.”

Going back to the days of the pocket watch, throughout the foundation of the Japanese watch industry, during the quartz crisis and after the release of the Apple watch – Swiss still means best.

But how did that happen? Despite all of the competition in the early days from the French and Dutch watchmakers (who, at one point, were the clear leaders in innovation), the Swiss are the world leaders. Let’s see how that happened.

The Early Days of the Swiss Watch Industry

The Swiss weren’t the first nation to make clocks small enough to carry around, that distinction goes to Germany. The first miniaturised clocks which could realistically be called watches were created somewhere between 1509 and 1530 (the earliest known watch was made in 1530) by Peter Henlein in Nuremberg. At over 3 inches long, the clocks were portable enough to be worn as items of clothing, but a little too big to fit in a pocket. Being incredibly rare and expensive, they were limited to being owned by the nobility at the time – as no-one else could afford them!

The Swiss watch industry started shortly afterwards , as the reformation started to change Western Europe (the religious revolution which started in 1517 by Martin Luther), the French Wars of Religion led to widespread persecution of the Huguenots (French protestants). Many Huguenots fled the persecution in France and entered Switzerland, bringing their clock and watch making skills to Geneva. This influx of skilled refugees helped transform the reputation of Geneva into a city known for its high quality watchmaking.

A huge revolution was already underway in Geneva at the time, led by John Calvin. The revolution in Geneva was heavily influenced by the reformation and made it a great place for Huguenots to integrate into the city. This revolution was also a perfect breeding ground for the clocks and watches which were being developed in Geneva.

As part of the changes Calvin was making in Geneva, there was much heavier regulation into people’s lives. Despite being well known for the Jewellery which was produced by the skilled goldsmiths in the city, wearing Jewellery was forbidden in Calvin’s Geneva. This destroyed the businesses of all of the goldsmiths and enamellers in Geneva, who steadily turned towards watchmaking. Goldsmiths and enamellers in Geneva, who had the expertise in beautiful design and craft, worked with the skilled Huguenots who had the knowledge and technique to create clocks and watches.

Finally, when the amount of regulation in Geneva was relaxed – around the end of the 17th Century, the city was known for its watchmaking expertise. Now that people were allowed to wear Jewellery again, the watchmaking expertise could be paired up with the decorative art that the city was traditionally known for. In a short time the Swiss watches produced in Geneva were not just known for their skill and quality watchmaking, but also for their beauty.

The Road to Dominating the Watch Industry

Of course, at this point, despite a good reputation – Swiss watches were not yet the standard by which all other watches would be judged. In fact, during the 18th Century, that label would probably be applied to watches produced in Britain.

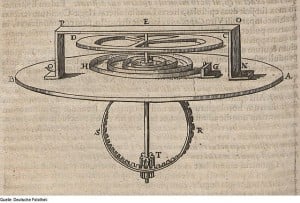

Pocketwatches were very popular in Britain at the time, the reason for this is usually attributed to the introduction of waistcoats. Because of this popularity, there was a lot of time and effort invested in the development of watches. Developments in manufacturing, including the tooth-cutting machine – which was devised by Robert Hooke, helped increase the volume of watches produced. While the inventions of the balance spring (arguably invented in either Britain by Robert Hooke or the Netherlands by Christiaan Huygens), chronometers and the lever escapement helped increase the accuracy and quality of watches.

Specifically in Britain, innovations from James Cox, John Harrison and George Graham paved the way for the kind of mechanical movements you see today. We’ll explore the British watch industry and the way the 18th Century innovations impacted today’s industry in a future blog post.

Whilst the British appeared to lead the way in innovation around this time, a lot of work was going on in Switzerland. Watchmaking spread across the Jura mountains, where the industry flourished. It wasn’t just innovation and excellence in terms of the watches developed, but also in the way watches were produced.

Much of the early innovation in the Jura mountains came from Daniel Jeanrichard, a goldsmith who was the first to apply the division of labour to the watchmaking industry. By using this to increase efficiency and standardisation he was able to increase production volume and quality. By the end of 1790 Geneva was already exporting over 60,000 watches!

Today Jeanrichard is considered the “founder of the watchmaking industry in the canton of Neuchâtel.”

More Swiss innovations came about over the following years. Abraham-Louis Perrelet created the “perpetual” watch in 1770, this watch was the forerunner to the modern self-winding watch. Adrien Philippe, one of the founders of the well respected brand Patek Philippe, invented the pendant winding watch. The fly back hand was developed in the Jura mountains around this time, too.

You also cannot forget the invention of the tourbillon by Swiss-born Abraham-Louis Breguet in 1795 (patented in 1801). One of the most incredible pieces of high-quality watchmaking expertise, although not one which is, or ever has been affordable enough for most people to own!

The invention which allowed the Swiss to gain control of the watch industry wasn’t actually developed in Switzerland at all. In the 1760’s French watchmaker Jean-Antoine Lépine invented a simplified flat calibre which became known as the Lépine calibre. This calibre allowed the development of smaller, thinner pocket watches. Horological historian David Christianson explained how this ended Britain’s dominance of the watch industry -“At that time, men’s fashion — thin trousers, waistcoats — demanded a nonbulky watch case… and the Brits weren’t willing to thin their watches.”

Jean-Antoine Lépine was part of the French watchmaking industry – in fact, serving as watchmaker to Louis XV, Louis XVI and Napoleon Bonaparte. However, his invention helped to create the Swiss watchmaking powerhouse which was set to dominate the industry and almost destroyed the French watchmaking industry. In the early 1800’s the Lépine calibre was adapted to factory production by French watchmaker Frédérick Japy. This development favoured Swiss watchmakers more than it did the French as Swiss farmers and peasants would spend their winter months making watch components for firms in Geneva. As further technology was implemented for mass-production, Swiss watchmakers were able to produce watches at much higher volumes than their rivals.

On top of that, the mass-production which was embraced in Switzerland was completely rejected in France. English and French watchmakers were unable to compete with the volume or price of mass-produced Swiss watches. The English watch industry almost collapsed at the end of the 1800’s and the French industry only just survived with a small number of indivuduals creating quality authentically-French timepieces.

Dominance Using the “Établissage” System

The way Swiss watches were developed was incredibly different to that used by their European neighbours. Jérôme Lambert, chief executive of Montblanc, thinks that the way the Swiss watch industry developed was a natural extension of Switzerland as a country. “As a country, Switzerland is very decentralized. Every valley has an owner or organization that has a dynamic, small city centre,” he explained. “That created a very natural extension of the traditional watchmaking way. It was not the same case in England, Germany or France, where it was very much centralized in big cities.”

Swiss watch manufacturers used a watchmaking system called établissage, which allowed them to develop watches much faster than any of their rivals. According to WorldTempus, this means “A procedure for manufacturing the watch and/or movement by assembling its various component parts. It usually involves the following operations: acceptance, inspection and storage of the Èbauches, regulating organs and other parts for the movement and exterior; assembly; timing; fitting the dial and hands; casing; final inspection before packaging and dispatching.”

In practise this means that different parts of the watch would be manufactured in different places, then assembled by the manufacturers to create the finished timepiece. Which is something that is still embraced by the lower priced Swiss watch manufacturers today with parts developed in the far east then assembled in Switzerland. By using this system, the pace of Swiss watch manufacturing increased in an almost unbelievable fashion.

In 1800, both Switzerland and Britain produced 200,000 timepieces, in 1850 Switzerland were able to produce 2,200,000 – while Britain produced little more than 200,000.

However, at this time a higher volume of Swiss timepieces did not mean higher quality. In the same way that countries like China and Thailand are able to create a huge number of watch components cheaply and quickly today, quantity doesn’t always mean quality.

Many Swiss watches would look just like watches manufactured in France or Britain, albeit with lower prices and wider availability. But the quality wouldn’t match up to the handmade originals.

This strategy worked for a while, but was disastrous when they attempted to break the lucrative American market, who were having a watchmaking boom of their own (which we will cover in a future blog post). They flooded the market with cheap Swiss watches which were widely considered to be “junk” by Americans.

Combining Mass-Production With High Quality

Despite the Swiss history of quality, if it wasn’t for the American optimised production process being implemented in Switzerland it’s very likely that Switzerland would not be the watchmaking powerhouse we know them to be today.

There were quality Swiss companies still putting out great quality watches, but they were eclipsed in number during the mid-1800’s by companies churning out cheap, low-quality watches. Over in America the optimised production process ensured that all watches were reliable, but they lacked the historical watch-making know-how and beauty of Swiss watches.

In 1868 Florentine A. Jones moved from America to Switzerland and founded the International Watch Company. This was an early company who succeeded in combining Swiss know-how and American production. It was also the start of some Swiss companies moving away from établissage and bringing all of their production in house. Longines, for example, brought their operations in house in 1866 and employed over 1,100 workers within 45 years.

By moving away from watch pieces being produced around the country then quickly assembled and towards optimised in-house production, the Swiss watch industry were able to keep production numbers high and retain their reputation for quality.

Of course, none of this would be possible if it wasn’t for research and inventions from Pierre-Frédéric Ingold and Georges-Auguste Léschot. Léschot is the most well-known of the two men – he invented one of the first machines to manufacture various parts of watches in order to obtain interchangeable parts.

Ingold is less known, but in some ways, probably more important. Ingold was involved in the development of a lot of quality French watches of the early-1800’s as an apprentice to Abraham-Louis Breguet, but his lasting innovation came in the machines used to mass-produce watches. In the 1830’s Ingold believed that watchmaking had gone as far as it could in the 19th Century without some kind of mechanisation. Because the machinery didn’t exist yet, Ingold decided to make it himself!

Ingold developed machinery to produce plates with sinks and jewel seats, machines for barrels and even more watch parts. He moved to England where his attempts to bring machine-manufactured watches were opposed by the establishment, leading him to move to the United States where his inventions had a huge influence on watch factories in the Boston area.

After returning to France and then Switzerland he continued to invent. Many of his inventions and techniques were implemented, – like the “Ingold fraise” (which is used to correct the profile of gear-wheel teeth) and a new type of a escapement he created in 1852. These inventions and techniques were vital in allowing the Swiss industry to move towards in-house optimised production. Ingold’s influence in America was vitally important in changing the Swiss industry, just as much as his inventions in Switzerland were important in allowing the industry to change.

The inventions from both Ingold and Léschot helped Switzerland extend its supremacy in the watch industry worldwide at the turn of the century. We’ll look at the how Switzerland dominated the watch industry in the early 20th century and the challenges they faced as the century went on in part 2 of The History of the Swiss Watch Industry.

Images: Joe Haupt, Modano~commonswiki