Watchmaking history shows a long history of rivalry between Japanese and Swiss watchmakers. The rivalry began when Japanese watchmakers became the first threat to the Swiss monopoly on watch manufacturing and was at its hight during the quartz crisis in the 1970’s.

But are you aware of the Swiss history which lies underneath the history of Japanese watches? Despite the historic rivalry between Japanese and Swiss watchmakers, the story the development of early Japanese watches is one of Swiss and Japanese cooperation, rather than competition.

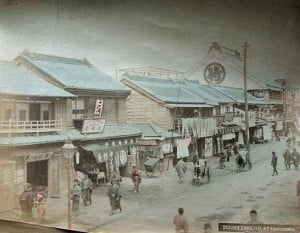

The First Swiss Watches in Japan

Swiss watches first appeared in Japan in the 1860’s, following the Friendship and Trade Treaty signed by the Swiss and Japanese governments in February 1864. Interestingly, Swiss watchmaker François Perregaux had actually already been trading in Japan since the turn of the decade that this treaty was signed.

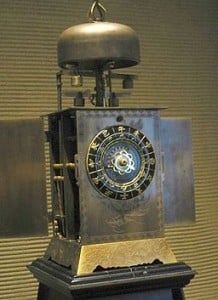

One significant problem with the import of Swiss watches at this time was the time system used in Japan during this period. Japaense clocks at this time are called wadokei (和時計) and used unequal temporal hours, 6 for the daytime and 6 for the nighttime. The daytime hours would be longer in summer, while the nighttime hours would be longer in winter.

When Swiss watches were first imported into Japan, they served no real purpose in terms of telling the time – as the Japanese did not use the same timekeeping system as the Europeans. The watches did become objects of curiosity for the Japanese, a glance into European culture which they had been cut off from ever since the 1600’s.

While this curiosity might have sparked interest in those who caught a glimpse of the watches, it wasn’t useful for people attempting to create a thriving Japanese watch market. That was the intention of François Perregaux and Edouard Schnell when they set said to Japan in 1860. Edouard Schnell was a Dutch national, which was vital if Perregaux was to forge any kind of trade with Japan.

The Japanese period of isolation had began in 1636, at which point Japan cut all links with the rest of the world. All non-Japanese nationals were expelled from the country by 1639 and all Japanese nationals were banned from leaving the country. The only exception to this was with the Dutch, thanks to their help quashing a rebellion, who remained the only country Japan would trade with.

Thanks to his nationality, Edouard Schnell was able to arrange the deeds to a land grant which allowed them both to open an office in Yokohama on behalf of the Watchmaking Union. Of course, due to the Japanese time system, creating a Japanese watch market was an incredibly difficult exercise, as this excerpt from a report they sent to the Watchmaking Union in 1861 shows:

“The sale of watches was very difficult. The Japanese did not use them; only a few Customs officers, who due to the dealings that they had with Europeans, had to know the time. But the difference that there was between the Japanese system and our way of reckoning time, the luxury that it was for a Japanese to buy an item costing 40 to 50 Itzibus, while all the clothes on their back cost 3 to 4 Itzibus, meant that watches could not be sold in big quantities, and it would be a long time yet before this article had the success that it enjoyed in China.”

While the curiosity and luxury that Schnell and Perregaux speaks of helped them sell some watches, even this source of sales was never going to last, as they explained in the same report.

“Musical items, watches, clocks, fancy items, jewellery etc. were never mass consumption goods: these articles were sold at very high prices, and as objects of curiosity rather than utility ; as imports of these articles grew in number, they ceased to be objects of curiosity, and prices fell; soon selling them became nearly impossible.”

The office they opened was liquidated by 1863 and the Watchmaking Union was dissolved by 1865. Schnell and Perregaux stayed in Japan and carved out a niche importing European goods to Japan, but an emergence of a booming watch market in Japan was going to need to wait a little while longer.

The End of Temporal Time

After signing trade treaties with Switzerland and America, Japan started to modernise at an incredibly fast rate. Links with the Dutch throughout their period of isolation allowed the Japanese to keep up to date with technological advances in Europe, meaning they were able to modernise much quicker than an isolationist country would be expected to.

In 1868 Japan abolished their temporal hour system and in 1872 moved from the lunar calendar to the western solar calendar. This change drove the need for a western-style clock industry and with it, the opportunity to drive a watch industry in Japan. At this time the only country with a watch industry was Switzerland – and many Swiss traders had already made a base in Japan, ready to take advantage by importing Swiss watches to the Japanese public.

As already mentioned, François Perregaux was already in Japan, but a the time of the switch to the solar calander both James Favre-Brandt and Siber-Brennwald were also trading in the country. They imported Swiss watches and sold them on to Japanese businessmen who distributed them throughout the country. The watch industry in Japan grew incredibly quickly, between 1880 and 1900 the amount of watches imported to satisfy demand more than trebled from 47,000 to 145,000.

The Early Emergence of Japanese Watches

One of the first Japanese watchmakers was Kintaro Hattori, who’s was the founder of the company which went on to became the Seiko corporation. You can read all about the incredible story behind the Seiko corporation in last weeks feature. He started his company by importing Swiss clocks and watches, before opening his own factory and producing Japanese-made watches in the 1890’s.

An interesting note to add onto last weeks story, is that Kintaro Hattori’s watches were produced with the help of engineers trained in a watchmaking school in Le Locle, the birthplace of the watch industry. One of the problems faced by Hattori during this time was the cost of watches produced in Japan, in order to make a profit on Japanese produced watches, they needed to be higher priced than imported watches. Hattori overcome this obstacle by negotiating rises in Japanese customs duties through his political connections, the import rates on gold watches rose from 5% before 1899 to 50% in 1906.

Swiss importers responded to this by starting to import kits of unassembled parts, which weren’t taxed at such a high rate, to be assembled in Japanese workshops. Hattori was someone who benefited from this practise as he purchased some of these parts. The worry in Switzerland is that it lead to Japanese-produced watches forcing Swiss watchmakers out of the country and potentially spreading worldwide.

One company particularly concerned about the potential danger for the Swiss watch industry from this practise was Rolex. Swiss watchmaker Tavannes Watch had kits assembled by 2 Japenese watch manufacturers in the early 1900’s and they considered opening a movement factory in Japan in 1932. Rolex strongly disapproved of this idea and made this very clear in their letter to the Federal Office for Industry, Crafts and Trades and Labour:

“Once a movement factory is established in Japan by a Swiss company as large as the one in question, we can say goodbye forever to Swiss articles for the East and the Far East. After a few years these [Japanese-made] models will spread around the world.”

The Breakthrough for Japanese Watches

Even though the prediction of Rolex seems fairly over the top, it is actually what ended up happening with the company who went on to become Citizen . Swiss born Rodolphe Schmid moved to Yokohoma in 1894 at the age of 23, quickly building a reputation as one of the top watch merchants – becoming the third largest importer within a year.

Schmid owned a factory in Neuchâtel where he was born, which was named Cassardes Watch in 1903. In 1908, due to the ever increasing import tax costs, he began to import kits and assemble them in a workshop in Yokohoma. Up until 1913 nothing was actually manufactured in Japan, but in that year he relocated the manufacture watch cases to Japan, which caused outrage in Switzerland.

The Neuchâtel Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Labour made their feelings on this development very clear in a letter to the Federal Department of the Economy where they denounced: “the selfishness of such an approach, as well as the grave harm that Swiss citizens, who have learned the trade in our country, can do to our watchmaking industry by setting up a factory for producing silver watch cases.” However, the manufacturing in Japan was restricted to watch cases, even as the factory grew in size, all movements were still imported from Switzerland.

That changed in 1930, when a merger between Schmid and the Shokosha workshop led to the opening of the Citizen Watch Company. Shokosha was founded by aspiring watchmaker Kamekichi Yamasaki in 1918. Yamasaki had travelled to Europe in 1911 and the United States in 1915, returning with tools from both countries. His workshop produced its first pocket watch in 1924 and he ran a watchmaking school, but the company was declared bankrupt in the late 1920’s.

Officially Schmid was only able to acquire 1.5% of the shares of the new company, although he was able to still retain indirect control of the new company through the managers of his own factory.

In 1930 Citizen Watch began operating in the Schmid factory, initially assembling parts for Shokosha. These did not sell very well and the company operated at a loss for the first 3 years, being propped up by the Yasuda Bank. Worker discontent was another big issue faced by the new company, culminating in a strike in 1933.

The big turnaround for Citizen was in the development of wristwatches, which Schmid had a huge role in.

The Swiss Origins of Citizen Wristwatches

Without Schmid’s involvement with Citizen, chances are that the company would never have improved their situation, such was the importance of his technical assistance. He imported machine tools from Switzerland in 1933 and had an engineer in Geneva draw up plans for new calibres in 1934.

Another company part-founded by Schmid was acquired by Citizen and this company was invaluable in the development of Citizen Wristwatches. The Star Shokai company was acquired in 1932, which was set up in order to import Swiss Mido watches into Japan. The 3 wristwatches produced by Citizen between 1931 and 1941 were all copies of Mido products.

A new factory was built in 1934 and they began to export to China from 1936, proving that there was some base to the fears of Rolex. The effect of Japanese-produced watches had already marked impact on the import of Swiss watches. In 1939 Hattori (Seiko) produced 1.3 million watches, Citizen produced around 248,000 watches, while Swiss imports had reduced to less than 50,000 units.

By this time, however, Schmid had left Japan and was back in Switzerland, but was still involved with Citizen – appearing on the shareholders list in 1948.

Citizen Post-Schmid

Following the war the Japanese watch industry boomed, with both Seiko and Citizen at the forefront of the industry. You can read about Seiko’s growth into a company respected worldwide in last weeks article. But, as for Citizen, their growth relied on continued work with watchmakers around the world. Working with companies like Bulova and Méroz throughout the 1960’s helped Citizen to become one of the top watchmakers around the world.

Since 1986 Citizen have been the world’s largest watch manufacturer, this position was cemented after acquiring Bulova in 2008.

None of these developments would have ever happened if it wasn’t for the early attempts to bring watches to the Japanese market. The booming Swiss watch import industry in the late 1800’s led to the assembly of watches in Japan, which led to the manufacture of watches in Japan. While Japan and Switzerland are watchmaking rivals now, the Japanese watch industry is built completely on Swiss foundations.

Images: Arjan Richter,